(This is the second in a post series that starts here)

My story with Image Generation starts with DALL-E, and so I will start there. I then cover Stable Diffusion and Midjourney before heading into some thoughts — It’s hard to call what I have a conclusion, since I feel so utterly inconclusive about this technology. (Note: Many of the galleries below have captions and commentary)

DALL-E 2

A painting of single poplar tree in fall with leaves falling, lit just before golden hour, that evokes feelings of nostalgia and warmth. This was the prompt that gave me my first result from DALL-E that made me go "oh shit."

It's not a perfect painting; there's certainly some oddities… but this looked way better than it had any right to be.

How did I get here?

I was creating slides for my CMPUT 229 class, and I was discussing one of my favourite assembly mnemonics, eieio, which always puts the song "Old Macdonald" in my head. The slide was a bit barren, so I thought, it would be nice to have some art for this. I'd just been reading a bit about DALL-E, and so I signed up for an account, and after a bit of trial and error had an image I could use for my class.

“A fine art painting of a farmer holding a microprocessor"'

The experience of playing with DALL-E was interesting. The prompts they display on the front page are often very simple things, producing surprisingly coherent results. In reality, excellent results seem to take a bit more effort than the simple prompts they propose — that or this is a question of luck, and access to many many generations for the same prompt.

DALL-E intrigued me heavily, so I played with it, up to the limit provided by their free credits. If you’re even remotely interested in this stuff, I’d encourage you to play with this as well. Even if you find the whole idea viscerally upsetting, it’s worth playing to figure out the strengths and weaknesses — and to be sure, there are weaknesses.

Of course, I opened this post being impressed: There certainly were a few results I found impressive. Even in failure, DALL-E often produced images that were nevertheless aesthetically pleasing (for example, I quite like the failed John Constable painting above).

Unfortunately, the limited credits that came for free with DALL-E limited my ability to explore these systems. I sought out other choices, and the obvious next thing to explore was…

Stable Diffusion

Stable Diffusion is an image generation where the model has been released publicly; this has lead to a number of implementations of the algorithms and apps that have wrapped everything up making it possible to do local generation.

My experience with Stable Diffusion has largely been that the results are not quite up to par with what DALL-E can provide. Partially this is because the model is optimized for producing 512x512 images, where DALL-E does 1024x1024. But more generally I’ve found that prompts the produce lovely results in DALL-E don’t produce results nearly of the same quality with Stable Diffusion.

Having said that, the ability to iterate has been interesting. I’ve played with two wrappers around Stable Diffusion; DiffusionBee and Draw Things AI (very powerful, but I’m not going to lie, the interface is baffling), as well as a python library (the one that powers DiffusionBee I think?)

Perhaps the most interesting thing I’ve found with these tools is the ability to play with parameters. For example, you can use the randomness generation seed, but vary your prompt, to interesting effect:

Notice how the composition mostly stays the same; this is side effect of the same starting seed. Using a command line version of Stable Diffusion, I have done a bit of larger scale experimentation with prompt changing while holding the seed still, producing some interesting effects

“Still life of hydrangeas, artist born around X”, for X in [1400, 2025] in 25 year increments…

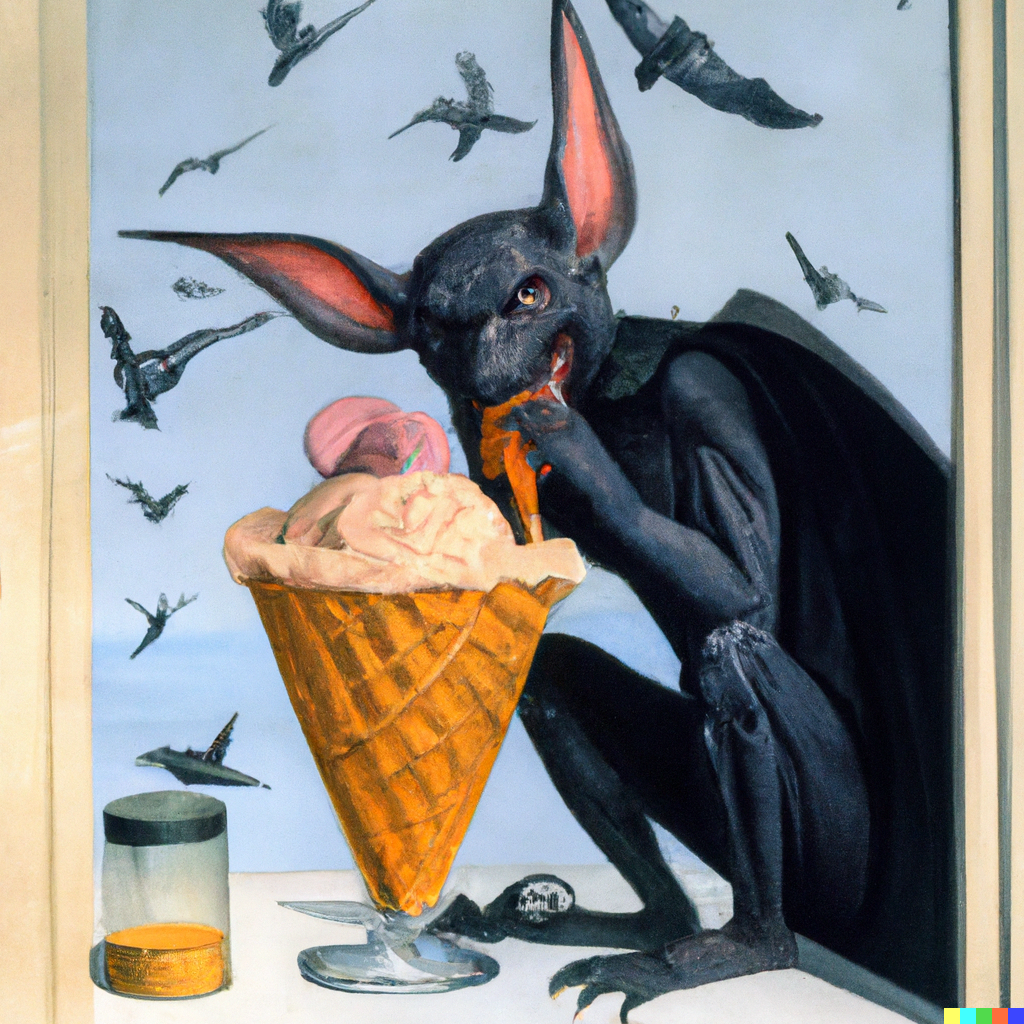

Another interesting parameter exposed by these tools is the “guidance” parameter, which as I understand it controls how much the model tries to take your prompt into account. Using 0 (don’t care about my prompt) has produced some wild images:

Midjourney

Midjourney is hard for me to write about, because I don’t understand it. It’s extremely clear they’re doing something clever, as Midjourney can often produce the most remarkable images from the simplest of prompts. Take a brief look through the Midjourney showcase, or look at these (deservedly!) New York Times Feature Article worthy images. Yet I have no idea how or why it works the way it does. I also find it painful to explore, as the interface (at least for free users) is a very noisy set of hundreds of channels on Discord; nothing like experimenting in public.

Despite the discomfort of working in public, it’s interesting to see what others produce. Some prompts are simple, some are complex, but I’m almost uniformly impressed by the results produced by Midjourney.

If I were an artist, Midjourney would be what scared me most — it’s clearly pulling modern styles from artists and reproducing them, sometimes with upsetting fidelity; showing Andrea the gallery and she said “it reminds me of my instagram feed”.

Someone described AI art as "discovery"; which does feel at least a bit apt; having said that, Midjourney has torqued itself incredibly to hit certain aesthetics with minimalist prompts.

Conclusions

It seems pretty clear that the ability to generate “good enough” art is going to have some very wide ranging impacts. As I said in my first post; the discussion of this is extremely challenging to separate from Capitalism. Some people are going to lose their jobs; more as these models get better. Will new jobs be created as a result? It seems to me that this is yet another automation that eliminates a class of jobs, making a smaller number of more valuable positions; another brick on the pedal of inequality.

I haven’t even touched on the questions of art and artistry here: Are the products of these systems art? Art prompt writers artists? Perhaps another post for another day…

Assorted Observations & Notes

My understanding of Stable Diffusion is that the model was trained on a data set released by LAION. There are a couple of tools to explore the data set used to train Stable Diffusion. I’ve played with this one, described here (note, there is NSFW content). Something that truly surprised me was the low quality of the captions. I had really expected that to provide good results the models would need excellent structured captions, yet it’s clearly not the case.

All these models thrive on the constraints provided by giving them an artist to ape. Looking at galleries of AI generated art, like the Midjourney Showcase and you’ll see a good number of the prompts including artists by name, sometimes many of them. For some reason “by Van Gogh” doesn’t nauseate me nearly the way “by Greg Rutkowski” does: this may just be the question of Capitalism again. There are already horrifying stories of models trained on single artists.

In a sense, my feelings about these programs are not directly affected by how they’re implemented; yet I find myself compelled to figure more out. I have only a rough understanding at the moment of how these systems are trained and deployed.

This blog series by Lior Sinai, though I’m only through part one, seems very promising. It’s pushing my math skills though.

These models are far from the end of this work; Google has Imagen, Imagen Video, and Imagen Editor baking. Impressive results. The section on “Limitations and Societal Impact” is a worthwhile read: “There are several ethical challenges facing text-to-image research broadly. We offer a more detailed exploration of these challenges in our paper and offer a summarized version here. First, downstream applications of text-to-image models are varied and may impact society in complex ways. The potential risks of misuse raise concerns regarding responsible open-sourcing of code and demos. At this time we have decided not to release code or a public demo.”